There are consequences to inaction. Especially when that inaction comes from people in power—people trusted to speak up, make decisions, and care for others in vulnerable positions. In the world of healthcare, silence is not neutral. It can be devastating.

My time under the care of the University of Chicago’s medical system taught me that even brilliant institutions can fail miserably when moral accountability is quietly set aside. Doctors often shield themselves behind clinical detachment, protocols, or the bureaucracy of large systems. But what happens when a patient is left to absorb the weight of their silence? When their non-decisions become life-altering events for someone already fighting to survive?

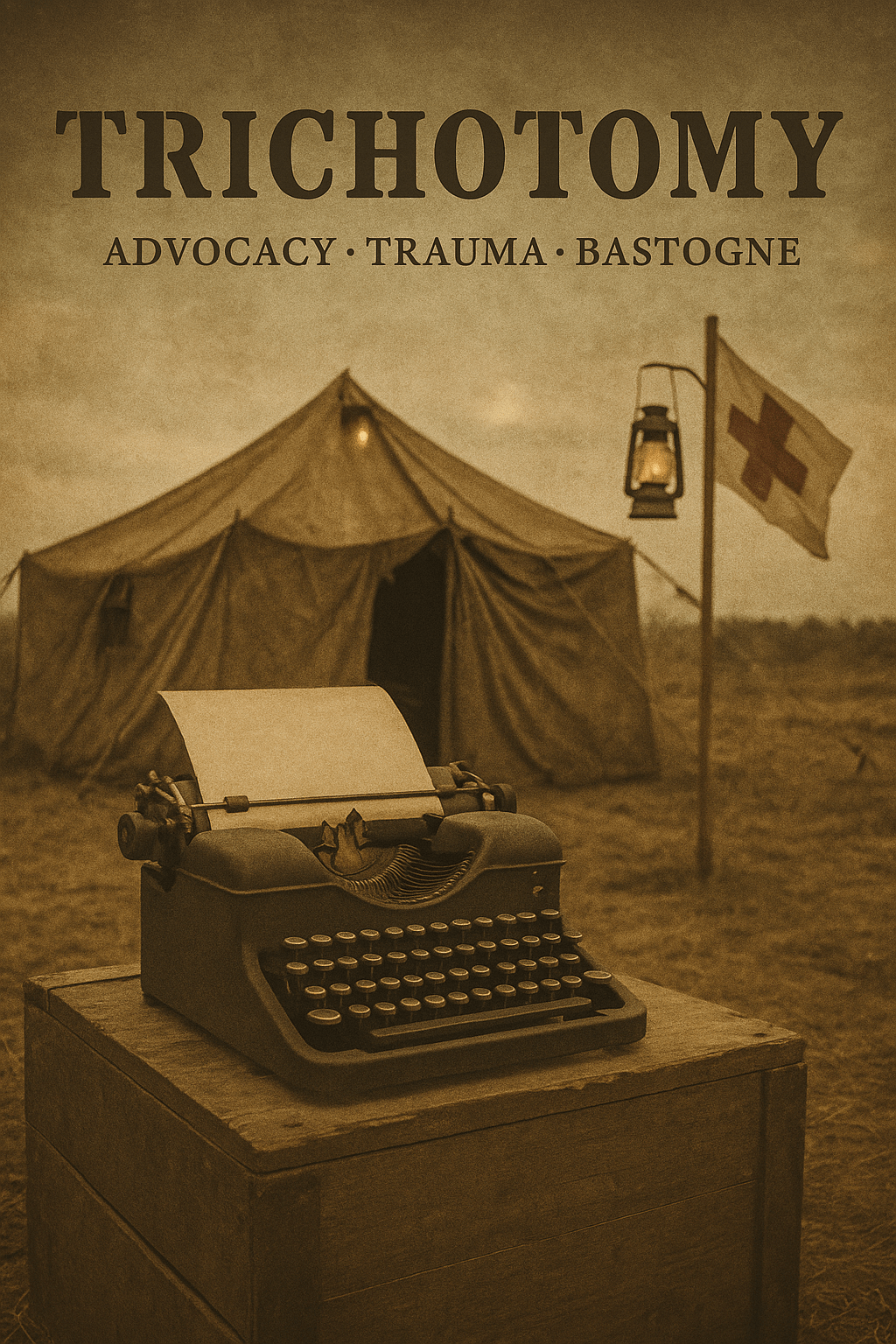

This is the story of what it costs to be caught in that silence. Of what I had to carry alone after those I trusted most looked away—or looked through me. Trichotomy: Advocacy, Trauma, Bastogne is not just a reflection on my medical journey. It’s a reckoning with the fracture between intention and action, between professional duty and human responsibility. It’s also an honest record of the toll that fracture took on my body, my mind, and my belief in the system I once trusted.

-CT

Trichotomy: Advocacy, Trauma, Bastogne

January 2024

Good morning from the middle of the west!

One of the blessings that came in my time of need in 2019 was my parents reopening their home to me. Mornings here often begin with birds singing sweetly in the trees behind my garage studio. My family’s property sits on a high point of the Fox River Valley, giving a clear line of sight to the river a few hundred yards below.

Two weeks ago, a snowstorm hit, making the roads impassable via Volkswagen. I had the rare treat of a snow day.

It’s inevitable when living at your parents’ place that moments of nostalgia sneak up on you. With the potential 2024 holds on my mind, I stood in our driveway with my tongue out catching snowflakes. I hadn’t done that in this place since many years back—well before the gray hair and troubles that came in adulthood. In that moment, with the snow quieting all that surrounded me, I finally knew in my heart it was a new season of life—and time to start living.

You see, in January 2023, I was in no mental space for such frivolity. My year was guaranteed to begin with a stoma revision, total proctocolectomy, and finally, the much-coveted end ileostomy. On 01/30/23, I would be making my fourth ER trip, hoping to receive treatment for what was now undoubtedly a bowel incarceration.

I feel for the audience (presumptuous to think anyone will read these, but nonetheless) that it’s important to share context about my experience with University of Chicago Gastrointestinal Disease Specialists. I came to them after being treated by Northwestern Medicine and Duly Health—under the care of Dr. Andelka Losavio (U of C grad, excellent and sincere doctor) and Dr. Michele Slogoff (Univ. of Texas fellowship-trained scientist, colorectal surgeon, and my medical confidant from day one of my clinical Crohn’s experience. She is a force to be reckoned with and one of the kindest souls). Dr. Losavio and Dr. Slogoff agreed I should go downtown for the best care. My situation was complex and severe. Complex Perianal Crohn’s Disease was the term I later learned described my symptomatology.

My first gastroenterologist in 2019 was Dr. Yogesh Patel from Illinois Gastroenterology Group. He was highly underprepared for the level of care I would require—but there is no coach for picking the right provider. My first post-op appointment with him was about biologic treatment. He came into the room, told me I had Crohn’s disease, handed me a list of three biologic treatments, and—without context or explanation—asked which one I had heard of and which I preferred for insurance approval. Humira was on the list. Thanks to Big Pharma’s marketing privileges in the U.S., that was the name I recognized, and so I picked it.

This gastroenterologist had received me from Dr. Michele Slogoff, a colon and rectal specialist surgeon. Yet, he gave no information related to this aspect of my condition or assistance when insurance denied the biologic. He prescribed azathioprine on its own, said to take four per day, and to call with any issues. I spent most of my first year as a Crohn’s patient without any biologic treatment—and without any meaningful discussion about the fact that perianal disease is not something to be treated by non-IBD specialists.

After months of no contact from that gastroenterologist, and with my surgeon growing increasingly concerned when I returned with another abscess, she referred me to Dr. Losavio. Dr. Losavio immediately initiated the Humira loading doses and, in that moment, showed me what supportive, responsive care truly looked like. I still credit Dr. Slogoff and Dr. Losavio with being the warriors who shifted the momentum of my care—and my life—for the better.

In September 2021, I had my first ostomy surgery to divert my bowel, with the goal of letting my rectum heal with less agitation. After that surgery, Dr. Losavio referred me to Dr. David Rubin’s practice. Due to scheduling, I was placed with Dr. Noa Cleveland. After our first two-hour intake meeting, I knew I needed to stay with this practice. Dr. Cleveland not only took notes on my health history—she paused to discuss concerns and affirmed that my Crohn’s journey had started in very deep water. I had never been affirmed like that by a doctor. She made me feel like the most important person in the room.

The reason the end of my time with University of Chicago was so painful is because, from that first meeting through the long, cold, hard crawl to my final surgery, Dr. Noa Cleveland was at my side—or at my back—pushing me forward. She told me on a phone call early on, “I’m your advocate.” Nobody had said that to me before. She helped place me on the Gastrointestinal Research Foundation Associates Board, which felt like an immense honor.

I ended my care with the University of Chicago due to multiple exceptionally negative interactions with their colon and rectal surgery team. Dr. Kinga Olortegui was the primary surgeon on my case. She was consistently aloof as our working relationship progressed. Unresponsive to direct messages or requests and the instigator of a conflict over imaging between the surgical team and gastroenterology team, her contributions only added stress and undue difficulty to my plan of care.

My condition was worsening and started to require hospital admittals through the ED when problems arose. Dr. Charlotte Harrington, a resident on shift during one visit, and an attending physician who accompanied her were also unreasonable and created a confusing scenario for a very sick patient.

When I arrived at UChicago via ambulance transfer from Central DuPage Hospital—at Dr. Olortegui’s direct instruction—I was placed in a room and did not see a doctor for over three hours.

When the attending finally entered, he opened with, “Mr. Taylor, Dr. Harrington and I are confused as to why you are here. You live in St. Charles. Do you have doctors here?” His tone was dismissive, and it was clear he hadn’t reviewed my chart or the circumstances leading to my transfer. He then conducted a rough exam of my stoma. While I had consented to being examined, the way he handled the situation felt unnecessarily forceful.

Before leaving the room, he patted my hand and said, “Keep losing those pounds. There’s nothing wrong with your stoma.” I felt small and silenced—entrapped in a system that showed little regard for the patient behind the case file.

Later that week, I asked Dr. Cleveland if I could be transferred to another surgeon. That request was never acknowledged. It was sifted away in the turbulence of that time, and my concerns with Dr. Olortegui were considered stress-related due to how intense the season had been. Given the severity of my condition, I felt I had no choice but to stick it out.

Throughout all of these experiences, I often felt internally conflicted and incredibly confused. I knew Noa was my advocate—we were on a first-name basis after months of navigating my complex issues. She also supported me as someone who genuinely cared, and I grew very attached to her.

I started to sense an undertone of conflict between the colorectal surgeons and the gastroenterologists. I leaned further into Noa because she was safe. I truly hate that taking a stand against the surgical team, combined with my own inner conflict and the fallout of recovery, resulted in the loss of that relationship. I wanted to be a part of what University of Chicago was doing, and Noa received me as an equal.

In my pain and anger, I asked to be transferred to another gastroenterologist. Due to Dr. Rubin’s awareness of my case and what had come before, he felt it best that I be treated elsewhere. He facilitated that transfer. I still feel rejected by my advocates. Codependency does weird things to the mind. So does unresolved conflict.

Trichotomy: Advocacy, Trauma, Bastogne

Do they relate to each other in some way? Absolutely.

Advocacy:

Dr. Noa Krugliak Cleveland was my advocate in the truest form. She was confident enough in herself to offer kindness and let a doctor’s heart for her patient be seen. This is rare. Dr. Michele Slogoff is the only other provider I know who offers this level of personal care.

Trauma:

My “trauma.” I still struggle with using that word to describe myself—or admitting how vulnerable I really was. It began early on, with Dr. Yogesh Patel and the erosion of trust between doctor and patient. Through counseling, I’ve come to understand that after ten surgeries, a global pandemic, being immunocompromised, and the betrayal of my own body—I had entered a post-traumatic stress state. Similar to many veterans I’ve spoken with, I too had mental scars from my war.

Bastogne:

Have you watched the HBO series Band of Brothers? The WWII-based series first aired in 2001 and has been one I revisit every couple of years. The episode “Bastogne” follows Easy Company as they’re surrounded and pinned down in the Ardennes Forest. Eugene G. Roe, the company medic, becomes embedded in the trauma, rescuing casualties while enduring constant bombardment.

The trees explode above their heads. Fear sets in. At one point, Donnie Wahlberg’s character “Lipton,” laughs in a foxhole—reminded of fireworks—until the screams pull him back to reality. The fog never lifts. Eugene makes regular trips to a nearby town hospital. There he converses and shares a quiet, human moment with a nurse who offers him a chocolate bar. But when he returns, the hospital has been bombed to the ground.

War is hell.

As a civilian, I claim no valor. But warfare and battling disease have many parallels. From 2019 through 2023, I lived under unrelenting pressure and anxiety—never knowing if I could trust my body. Flares, ER trips, infusions, altered plans. The barrage never stopped. COVID-19 added another layer—rewriting how we connect, how we heal, and how we trust. Nobody was safe from that wave. In times like these, we cling to whatever anchors remain.

How do we move on from times of sorrow and immense struggle?

There is no other choice—we must. How will be found in the steps that follow the first.

This story was once something I only whispered to trusted ears. But silence no longer serves me. These are pieces I’ve carried for too long. I share them not out of bitterness—but out of necessity.

The hope for reconciliation—or at least mutual understanding—still flickers quietly in the distance.

Leave a comment